About the National Book Award

Virginia:

I was traveling in China on September 11, 2001. On television in Suzhou, the city of tranquil gardens, we saw the planes, the flames, we thought the world had come to an end. We would later find out that some things, but not the world, had come to an end.

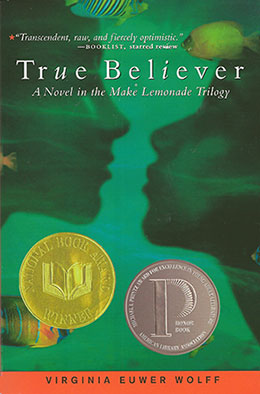

When Neil Baldwin, Executive Director of the National Book Foundation, phoned me just a few weeks later, telling me that True Believer had been selected as one of five finalists for the National Book Award in Children’s Literature, I said, “You mean you’re having the National Book Awards this year?”

He said, “Yes, we are. Now, more than ever, we need to honor literature…”

“Oh,” I said. I don’t think I was convinced. But I got ready to go to New York. My daughter and son would join me from their respective homes in the mid-Atlantic and New England. I would not buy a new dress for the black-tie dinner. To shop would be cruel. I would wear what I had.

Brenda Bowen, Virginia’s longtime editor:

November of 2001 and the city was still raw and bleeding from September 11. It seemed ugly and foolish to dress up and celebrate reading when so many people had died and the city had been bombed. But if there’s no National Book Award, do the terrorists win? That was the rhetoric of the day. We tried to put that aside and think about what the award meant to readers, to authors, to the culture. And we knew it had to go on. But what could we do to make the event mean something in November of that year?

A small group of us—Anne Schwartz, Paula Wiseman, Tamson Weston, Garen Thomas, Judy Cecco, some of whom are still very much in children’s book publishing —felt the NBA ceremony could give us an opportunity to raise money for World Trade Center victims. We had read that immigrants who had been undocumented when their deaths occurred were barred from receiving any aid—not from insurance, not from the government. A lot of the workers at Windows on the World restaurant were undocumented, and the owners of the restaurant set up a fund for private donations for the workers’ families. This felt like the place that needed our money most.

We called on the artists of the children’s book world for donations, and they gave generously of their talent. We staged a silent auction before the event, and the people who came to the awards ceremony that night were so grateful and glad to see us there. There was no cajoling, hardly a mention of the auction, yet we raised over $40,000 that night for the families of people who had died.

Virginia:

All National Book Award finalists were to be in New York one day early to take part in a finalists’ reading at the New School. An airplane crashed in the New York area while I was changing planes on the west coast. All flights were halted for several hours, mine in Seattle. I called Brenda, my editor, from a phone on the back of the seat in front of me to tell her the sections I wanted her to read from True Believer that evening at the New School if I didn’t reach New York in time to read them myself. The plane crash in New York turned out to be unrelated to the terrorist attack, and my flight arrived safely in New York, a few hours late. My son and daughter and I went to the New School reading, and it all seemed to be happening sideways: Each of us finalists read aloud from books we’d written that were utterly lacking in prescience about what would occur to change us all on September 11 of that year. The evening felt to me like a kind of ritual of pretending.

I had an immediate goal for the next day: to visit the gravesite of the World Trade Center.

Brenda:

Jinny, too, had spent the day in the shadow of the World Trade Center: she visited Ground Zero when it was a massive, gaping hole in the ground. Both of us needed perspective on the black tie event we were attending just weeks after the attack. So when the dinner began and the fabulous Steve Martin took the stage, we were both freed of the feeling that this was a live or die moment. We’d just lived through a real live or die moment.

Virginia:

I’m not so sure we had. I had not. My son and I had gone to the World Trade Center site and simply stared, mostly wordlessly, walking in the nearly silent crowd of people who had come there just as we had, to try to understand what could really not be understood. He and I didn’t mention the evening when we had celebrated his birthday at the Cellar in the Sky at the top of the World Trade Center. We paused at Trinity Church where a 24-hour relief center had been set up for the Ground Zero workers, and where New Yorkers had hung photographs of their missing loved ones, where bright flowers were placed between the pointed spears of the wrought iron fence. We read the posters, we walked, we walked, we wondered and murmured, along with everyone else. How to comprehend?

Back at the hotel, my daughter joined us and we put on the dress-up clothing we had brought along for the banquet. It began to occur to me that of five finalists one of us had to win. On the back of a business card I jotted the word “Faulkner” and the names of my agent, Marilyn E. Marlow, my editor, Brenda, my brother, my son and daughter. I still was seeing the Trinity Church fence with its flowers, its bank of posters: “Have you seen this person?” Somebody’s brother, father, daughter.

We went to the Marriott Marquis and the banquet.

Brenda:

When the head of the Young People’s Literature committee began reading her citation—which was carefully worded so that it might have fit any of the books—I knew with absolute certainty that the book she was speaking about was True Believer. Then she said the words, “True Believer, by Virginia Euwer Wolff,” and Jinny was out of her seat with her tiny piece of paper in hand. Up to the podium she walked, a National Book Award winner then and for always.

Virginia:

Actually, she said, “Thank you, Virginia Euwer Wolff, for writing True Believer…” and I don’t remember the rest.

Steve Martin held my hand. I said whatever I said. Marilyn E. Marlow, the dedicatee of True Believer, who was with us that evening, died the following summer, on my birthday, at about the same time that I was in King’s College Chapel in England, hoping for peace for her and the world.